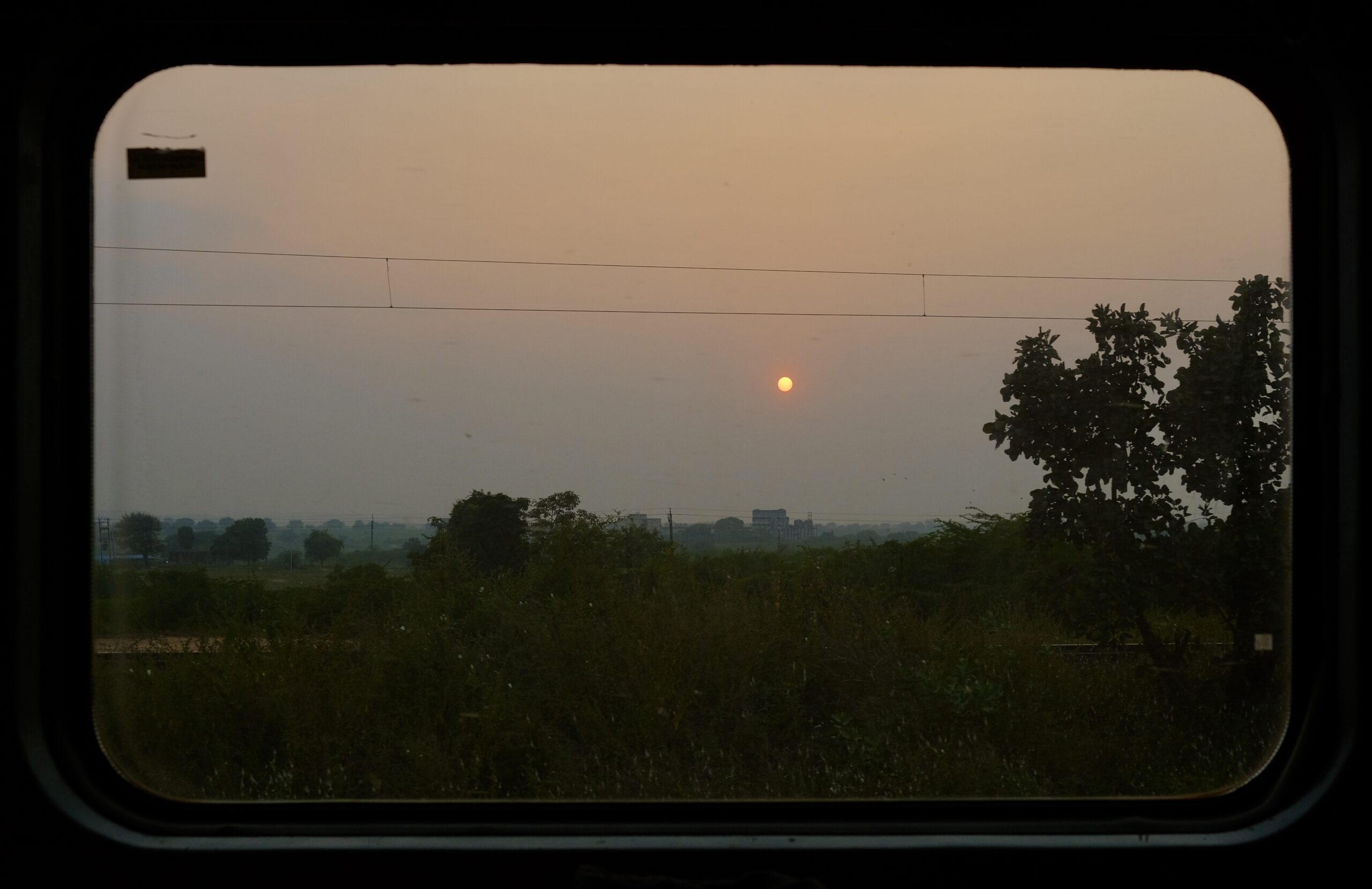

This is my first publication on this blog and it’s been quite some time in the making. As I am writing these lines, lush forested landscapes unravel beside me through the window of my train. The tropical evergreen forest is glowing in the orange morning light. Like most days in this part of the world, it is humid and hazy outside. This is quite a transition from the dry and cold high-altitude desert of Ladakh where I’ve been for the past few months. Luckily for me, it seems, the powerful AC aboard the Tamil Nadu Express has me keeping my scarf and wool socks on. So this 35-hour train ride will be an opportunity to acclimatize gradually to the unfamiliar heat and scenery. It will also be a time to reflect and write about the places and people that have become so familiar over the past few months.

Writing about Ladakh

Since I arrived in Ladakh, I have found it quite difficult to write about my Watson experience. Besides the technical problems related to creating a blog from scratch and living in communities with limited internet and electricity, the novelty of my learnings and experiences often made my thoughts overwhelming to process—let alone organize into coherent writings. Yet, I recently sat down and wrote a whole report for the Watson Foundation which taught me that processing and writing are not necessarily sequential. They can be self-reinforcing activities part of the same process. I know it might sound obvious to those used to journaling but I found it surprisingly difficult to do after having spent years writing theses and essays. So this first blog post is about starting a new process and getting slowly familiar with it. Just like boarding a train for a long ride into a foreign country.

Starting from the beginning

The first part of my Watson year was characterized by significant changes and setbacks to my initial plans. After an important call with one of my contacts in India, I decided to come earlier than originally planned to the Himalayas so I could participate in the autumn harvest work. It was presented to me a better way to integrate the community I was initially supposed to visit at the end of winter. As my plan to sail across the Atlantic had also been altered, it was an easy change. So I postponed my time in Europe to early spring and went directly to India instead. In retrospect, this was the best decision I could have taken. Autumn was a very special time to visit Ladakh and I don’t think I could have entered India if I had waited due to its current political conflict with Canada.

New Delhi

After landing in Delhi, I quickly realized that it wasn’t a place I wanted to stay long. I never liked large cities because of the heat, the pollution, the traffic, and the people harassing me on the street. Unfortunately, my first impression of Delhi was a condensed version of all that. I recognize, though, that my perspective was limited and that I might have set myself up for failure for not having done too much research. The consequence of that was being greeted in the city with an overpriced taxi ride going on unnecessary detours. Had I known that the Delhi metro was fast, safe and cheap, I would have saved myself lots of trouble (and twenty times the cost of a metro fare). Once I reached my hostel, what was supposed to be a convenient location to catch a train the next day turned out to be in a pretty bad neighbourhood. Luckily, I met very friendly young Indian guys who took me under their wings, helped me navigate the city’s craziness, and kept the pimps and scammers at bay. Without them, I don’t know how I would have survived Delhi. It taught me that like anywhere, Delhi has great and ill-intentioned people. You simply need to attract both so it can even out situations that could otherwise be problematic.

Towards the Himalayas

After leaving Delhi, I headed towards the Himalayas via the road going through Kashmir to try avoid altitude sickness. After a long journey to Srinagar, I stayed on a houseboat— a common form of lodging for tourists in the region— for a couple of days. To help me acclimatize, I went on a couple of day hikes to the lower Himalayan mountains and was struck by the beauty of the landscape and the hospitality of Kashmiris. I didn’t have much expectations going there and my host was surprised when I told him that I was just passing by. He took it upon himself that I left Kashmir with a strong desire to come back so he generously drove me around the lakes of Srinagar and brought me to the snowy caps of “little Switzerland” where I saw turquoise rivers, wild horses, and Gujjar nomads tending to their sheep. He certainly did a good job because I have kept thinking about Kashmir ever since.

During my time in the region, Kashmiris treated me with respect and friendliness which was a big contrast with the experience I had in Delhi. My host attributed this hospitality to his people’s strong morals and their reliance on tourism. He told me that Kashmiris took a great financial hit during the Covid pandemic as revenues from tourism ran dry. Some people could not afford to even feed themselves. For him, it was a reassertion of the strength of his community as people helped each other out. Since that time, he said, people seem much more aware that they depend on each other and that they depend on tourism for their livelihoods. Despite the bad press that Kashmir might have elsewhere in India, I had an amazing experience and never felt unsafe in this region.

A Hint at Regional Geopolitics

Something that quickly stood out during my time in Kashmir was the incredible militarization of the region. While I was there, we drove on highways riddled with outposts every 500 meters and went through countless military checkpoints. There were so many soldiers that at times I wondered if I was traveling into a war zone. Yet, people assured me that there was no violence going on. Not even potential threats of a conflict. The deployment of out-of-state military was an increasingly common occurrence in the region since 2019 when Kashmir was stripped of its semi-autonomous statehood in an political coup. Being curious by nature, I must have asked every single person I met about the region’s history leading to today’s army deployment. What came out of those conversations was a complex tale weaving together colonialism, development, and nationalism rooted in religious division. As I would later realize, knowing about these regional geopolitics is essential to understanding some of the complex relationships affecting the development of small communities in the Himalayan region. However, it will require a blog post of its own to properly expand on it.

Entering the Land of High Passes

Leaving Srinagar early morning towards Ladakh, I was feeling a bit nervous about the road ahead. My final destination was at least 2000 meters higher in the mountains but I knew that we would have to cross passes as high as 4000 meters on the way. Knowing that I tend to get car sick on winding roads, I apprehended experiencing high altitude sickness on top of it. In the end, the scenery and the adrenaline from zigzagging up steep mountain cliffs kept me well oxygenated and distracted from potential health inconforts. It was by far the scariest and most beautiful drive of my life.

During the 10-hour drive, I saw Gujjar nomads guiding their sheep herds towards green high pastures where wild horses could also be spotted every once in a while. Once we made it to Ladakh, however, the green mountains transformed into lunar-like landscapes of sand and steep grey mountains. In this high-altitude desert landscape, the most vibrant colours are found in the little oases around villages where golden wheat fields, bright green willow tree foliage, and apricot trees loaded with iridescent orange fruits could be seen from far away. Such abundance struck me in a place seemingly so hostile.

Tar Village

The final destination of this memorable journey was a small remote village named Tar. There, I was going to meet my contacts, Caitlin and Jason, two Americans living in the community who had been recommended to me by a professor at College of the Atlantic for their work with sustainable farming and traditional ecological knowledge in the Himalayas. They had arranged a place for me to stay in the village and would help me navigate the Ladakhi language during my time in the community.

I had been intrigued by Tar for my project on alternative regional development because of the community’s work on revitalizing their village after decades of rural exodus. Like many other remote communities in Ladakh, Tar is characterized by an aging demographic and a slow abandonment of traditional livelihoods. Today, very few young people still live in the village. They often left at an early age to study in cities where they later settled to have a family and work in the wage economy. Many years ago, the closure of the village’s primary school due to the lack of children made it all the more difficult for young families to eventually return.

Where I am from, we like to say that it takes the participation of a whole village to raise a child. These days, this phrase has me wondering: How many children are necessary to raise a village? Since I arrived in Tar, it has been clear to me that answering this question would be central to any efforts to revitalize the community. Yet, reducing Tar’s challenges to a simple demographic question would be a mistake. In a region developing rapidly to become integrated and connected to the rest of the world, small communities like Tar are continuously adapting to enormous economic, cultural, and environmental pressures. Such forces often come as threats needing to be mitigated and negotiated. However, there are times when these come as new opportunities to create alternatives and reimagine what it means to be a thriving remote mountain community in the 21st century. Over the past years, the people of Tar, particularly the youth, have began such an ambitious and experimental undertaking.

This is what inspired me to spend a few months with them.